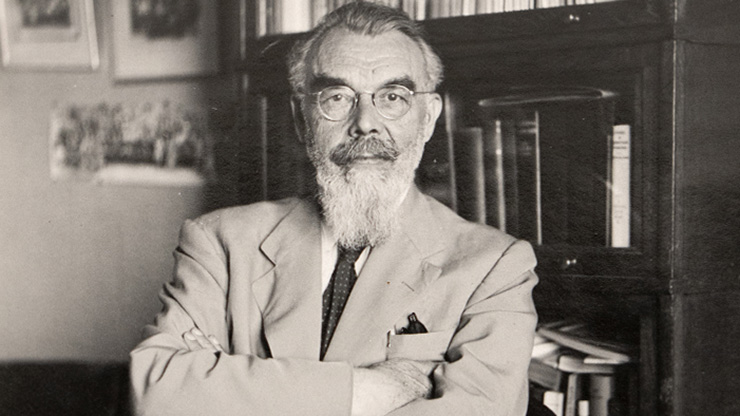

Adolf Keller (1872–1963)

Cosmopolitan, ecumenist, social ethicist, and mediator between cultures

“God gave me the time, health, and strength for all these tasks”

Adolf Keller grew up in a Pietist family in Rüdlingen, Canton Schaffhausen. As the eldest son of two teachers, Johann Georg and Margarita Keller-Buchter, mission and evangelism played a role in his life early on. Keller’s desire to share his faith and connect with the worldwide church would only grow. He completed his Gymnasium or secondary school in Schaffhausen and studied theology, among other subjects, in Basel and Berlin with Adolf von Harnack and Adolf Schlatter. He was already unhappy at the time with the fact that theology was divided into orthodox and liberal schools of thought.

After his ordination, Keller became an assistant pastor at the German Protestant Congregation of Cairo in 1896. Once there, he was able to deepen his knowledge of Arabic and the Koran. The inner divisions of Christianity in comparison with Islam pained him, even as he experienced meaningful cooperation within his own congregation that cut across denominational lines. Upon his return to Switzerland, three years later, he became a pastor in Burg near Stein am Rhein, then in the German-speaking congregation in Geneva, and subsequently at St. Peter’s in Zurich (1909-1923). He was convinced that, in addition to his duties to provide pastoral care, he needed to share in responsibility for church and society, especially in times of crisis.

He worked for the renewal of church and society based on early Christian models and inspiration from encounters with European and North American Christians. With a view to Switzerland, he was concerned that the Reformed churches did not form enough of a “real community” to be able to act socially, spiritually, and even politically. During the First World War, it became clear to the Swiss Church Conference that a more binding association had to be created for joint action, and it set up a permanent office in 1917. After the end of the war, the American Church Federation looked for a dialogue partner in European Protestantism and set its sights on a neutral Switzerland that was unscathed by the war. The Church Conference sent the worldly Keller to Cleveland and the 1919 General Assembly of the Federal Council of the Churches in Christ in America. A close relationship and collaboration would follow. Keller brought the idea of a federation back to Switzerland as a means of mastering the challenges of the post-war period and to cultivate common bonds, with Protestant, Orthodox, and Anglican Churches from abroad as well. The ecumenically-minded Keller then shaped the newly founded Federation of Swiss Protestant Churches as its secretary from 1920 to 1941 in a part-time position. From Keller’s point of view, the FSPC was intended to provide guidance in the event of conflicts of interest by referring to binding ecumenical obligations. It was also Keller who prepared the FSPC’s accession to the planned World Council of Churches in 1940, a move that did not go without criticism from within the organization’s own ranks. Beginning in 1920, he was a regular FSPC delegate to international ecumenical conferences and negotiated the accession of the FSPC to the World Alliance of Reformed Churches. Due to his extensive travel on behalf of the FSPC, Karl Barth gave him the nickname Weltadolf (“Adolf of the World”). As its second general secretary, he supported the work of the ecumenical Life and Work movement, which led to the founding of the WCC in 1948.

Keller was committed to the unity of Christianity all throughout his life. He recognized a core of spiritual life in all denominations and the dawning of an age in which Reformed Christians would focus more on what unites them with other Christians than on what divides them. His international ecumenical work and cooperation among the Reformed Churches in Switzerland was not an either-or choice for Keller. He believed that one benefited the other and was of theological necessity. In various publications, he worked to bring the German and English-language worlds of church and theology closer together.

Beginning in 1926, Keller headed the International Christian Social Institute (Life and Work) and served as a lecturer on ecumenical issues at the Universities of Zurich and Geneva. The Ecumenical Seminary founded by Keller in 1934 was the forerunner to the Bossey Ecumenical Institute.

As Secretary General, Keller headed the European Central Bureau for Inter-Church Aid in Zurich between 1922 and 1945. He made no fundamental distinction between church and political-social endeavors. Despite the terrible reality of the war and its consequences, the churches could “time and again maintain the belief that we, as children of one father and one earth, can escape the darkness of the present and move towards the coming community of love and justice”. The European Central Bureau also helped Orthodox students, assisted persecuted Armenian Christians and Nestorian Assyrians in Iraq, and provided aid during famines in Russia and China. This would later be followed by efforts for Protestant refugees from Spain in France. Thanks to his international connections and fact-finding trips, Keller was able to ensure that the funds were distributed well. With the help of Swiss bankers, he launched an international Protestant loan cooperative (now the Ecumenical Church Loan Fund, ECLOF). From 1933 onwards, the aid agency increasingly took care of Protestant refugees. The European Central Bureau was incorporated into the WCC’s Inter-Church Aid Department in 1945.

Keller pursued a great many interests throughout his life, wrote articles for various newspapers in addition to his ministry, grappled with the psychoanalysis of his friend Carl Gustav Jung as well as Henri Bergson’s philosophy of life. He devoted himself to his tasks with great enthusiasm and was cosmopolitan in spirit. He raised five children with his wife Tina Keller-Jenny, a psychotherapist by profession. He was an excellent pianist and loved Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms. Even after his retirement, Keller continued to pursue his academic work and participated, among other things, in the publication of the history of the ecumenical movement. In 1954, Keller emigrated to Evanston, California, where he would spend the rest of his life.